- Home

- Hoang, Jamie

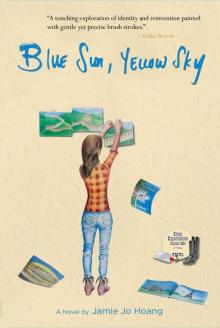

Blue Sun, Yellow Sky Page 10

Blue Sun, Yellow Sky Read online

Page 10

The Treasury, so named because people thought it held hidden vaults full of gold, jewels, and other precious metals, was the most famous structure in Petra. Carved purely from the rock, the structure was forty meters high, broken up into two tiers, and fit for giants, according to Atef. At the top was an urn, which many people believed to be the key to unlocking the Treasury.

For centuries, Petra was kept hidden because the Bedouin people were afraid western magicians might unlock the secrets of the storehouse and steal the wealth that belonged to the locals. Hundreds of years later, a treasure had yet to be discovered.

Jeff noticed me staring at Atef in the mirror and whispered, “Jesus, Aubs, you’re drooling.”

“Oh please,” I hissed. “I saw you at the bar last night.”

“What are we in high school again?” Jeff said, looking confused.

“What’s that supposed to mean?” I asked. Jeff said nothing.

“I have been a tour guide for ten years, how can I tell you for certain that no treasure exists if I have not attempted to claim it myself?” Atef continued, seemingly unaware of our backseat conversation.

Bold and candid. I was in heaven.

It was mid-afternoon by the time we reached our destination. “This is perfect time to arrive in Petra. It’s not as hot and we’ll be able to catch a beautiful sunset,” Atef said as he pulled into the parking lot. Getting out of the car with our small daypacks, we walked right past the ticket booth and straight to the entrance, which was a few hundred yards ahead.

As we passed by, I watched a French couple arguing heatedly with the ticket counter lady over the French woman’s immodest outfit: her strappy summer dress and sandals were a definite no-no. Jeff and I were both dressed conservatively: me in jeans and three-quarter sleeve crew neck t-shirt, and Jeff in a light gray, fitted t-shirt and drawstring pants. Atef had informed us of this dress code when we called to book the tour: no shoulders showing and long pants.

Shaking his head, Atef said, “That is embarrassing.”

“No kidding,” I added. “Who’s her tour guide?”

“By the way she is yelling, I would say it is her boyfriend,” he laughed.

Our tickets were waiting with a friend of Atef’s who had come early and stood in line so that we didn’t have to. This was a perk of having Atef that even Jeff could appreciate.

Once through the entrance, we followed Atef across the vast span of desert toward the facade of pink sandstone mountain ranges. There wasn’t much of anything in any direction; just endless mounds of red rock and flat desert. Then, as we got closer, I started to see it: a crack in the seemingly never-ending span of reddish rock.

It was as if a violent burst of lightning had struck the rock, leaving a crooked, narrow path through the mountain. This was known as the Siq and, much to my surprise, the walkway would continue for quite a while (1.2 kilometers). Jeff’s claustrophobia made this a little unsettling for him, but I was actually surprised at how open it felt for being such a narrow crevice. The tops of the rock opened up to a bright and cloudless blue sky, giving the space an aura of endless expansion. No wonder it was kept hidden for so long. Blink and I would have missed the opening.

Above us, Atef pointed at what looked like primitive gutters carved into the wall and explained that they were used to irrigate water from Wadi Musa to the city. I had no idea how far Wadi Musa was from Petra, but the system stretched farther than I could see. While the surface of it appeared primitive, I thought it looked efficient and aesthetically pleasing. Set well above eye level, the people would’ve had the ambient sound of flowing water as they traveled though the Siq.

Call it my imagination, or maybe my other senses rising in sensitivity, but I heard the water—I felt it, moving with a natural ebb and flow. Only, there wasn’t any water gesticulating. The only real evidence I had to go by was Atef’s description.

I pulled my digital camera out of my backpack to take a photo for color reference later. I snapped a couple of shots and then, for whatever reason, I closed my eyes and took another shot, and then another, and seventeen more after that. With the sun as bright as it was, the insides of my eyelids had a reddish hue to them, and as I moved my left hand along the wall, my right clicked away at images I couldn’t see. I brought my face closer to the wall and away from it, watching as the light darkened and brightened behind my still-closed eyelids.

“What are you doing?” Atef asked, causing my eyes to pop open in embarrassment.

“Oh! Uh, just taking some photos for my friend,” I replied.

“Do you know how to use your camera?” he asked, taking the camera from me. “You hold it up like this,” he instructed, putting the camera closer to my face so I could see the LCD screen. “And then you push this to make the photo.”

I laughed. “I know, I was just trying something different.”

“Oh. Yes, of course,” he said, looking slightly embarrassed as handed the camera back to me. “Do you know the story of Moses?” he asked.

“Vaguely.”

“As Moses led his followers through the desert, they became sick with thirst, and it was to our east, at Wadi Musa, that Moses’ cane struck the wall and released cool water for his people,” Atef said. He then went on to talk about how the pipeline promoted open channel flow and particle settling basins were designed to produce potable water supplies.

“I bet bottled water would’ve blown their minds,” I joked. Atef laughed deeply, which made me smile.

“I think there are more miraculous things than bottled water,” Jeff said. I looked over at him expecting to see a sarcastic smirk across his face, but he had already turned away. His lack of eye contact made his comment seem passive-aggressive. Maybe his claustrophobia was getting to him.

I waited a few minutes to give him space before saying, “I wonder if we’ll be able to find a ‘Moses was here’ etching somewhere on the wall,” and when he still didn’t say anything I wondered if he might be in the midst of a panic attack.

“Jeff, are you okay?” He nodded yes. “Are you sure? We can stop if you need to.”

“No,” he responded tensely. “Just need to get to the end.”

I patted him on the back and squeezed his arm, “Don’t worry. In 2,000 years it hasn’t collapsed. Maybe it will someday, but trust me when I say today is not that day.” He kept walking and I was about to say something else when the crevice opened up.

Before us was a 40-meter-high, hand-carved edifice on the red rock mountainside. Six enormous round pillars held up the two-tiered facade, which was so smooth it was a juxtaposition with the very rock from which it was carved. Centuries of erosion had stripped the facade of many of its original details. The large figures of Castor and Pollux, the sons of Zeus, had been carved between the lower pillars and, though preserved, they were difficult to discern without Atef’s help. Yet, there was no question the craftsmanship poured into the Treasury was extremely sophisticated given the rudimentary tools available at the time.

At the very top, underneath the flat fascia were the markings of bullet holes, as well as vague remnants of what used to be an urn. Unfortunate as it was for the urn to have been nearly destroyed in visitors’ quests for treasure, the destruction became a trademark symbol for one of the most fascinating stories in history.

“Which one is yours?” I asked Atef, pointing to the bullet holes.

He smiled wickedly, moved closer to me, put his hand on the small of my back, and pointed at the center of the urn. “It’s that one, in the middle, I hit it dead on and still nothing.” There was absolutely nothing flirtatious about his response and yet I felt myself blushing.

“I bet all the tour guides claim that bullet hole is theirs,” Jeff said. Atef seemed unfazed as he smiled and continued walking.

“What’s with the attitude?” I asked Jeff once Atef was out of earshot.

“He shot it dead in the middle? Yeah right.”

“He’s telling us stories. Who cares if he fibs where

his bullet hit?”

“He’s just trying to impress you.”

“So?”

“Okay then,” Jeff shrugged. He walked off towards the Treasury leaving me wondering what the heck had just transpired. I looked after him for a few minutes, expecting him to come back and apologize for his rude behavior, or at the very least come back with an argument, but he just kept on walking.

Giving Jeff space, I kept my distance and took photos of the unfinished Greco-Roman Treasury, which appeared like a stamp on the side of an enormous mountain. I say unfinished because the area surrounding it looked as natural as it probably had back when the facade was being carved. Rough and jagged spaces between smooth, finished ones meant the city had plans for expansion. Built to withstand the test of time, the carvings and pillars, though damaged, were still sharp at the edges and evenly rounded at the curves.

When I finally caught up to them, Atef continued his tour, saying, “This structure was carved starting at the top and working their way down. On the sides you can see the markings for the scaffolding still in place. It was designed to protect the bottom sections from being damaged while they hammered and chiseled into the mountain. You will see, all around Petra there are Greek, Roman and Egyptian statues. Here, these columns are Roman; up top, the carved goddesses were derived from Greek mythology; and on the sides, the winged eagles were Egyptian-influenced. Inside, you will see carved-out spaces where statues of the gods resided. Also, you will see seats carved out on the opposite side for visitors. Take a look around for a bit, walk inside and then we’ll visit to one other place before heading back to the campsite for dinner.”

“I’m gonna take a walk,” I said, looking at Jeff for some kind of clue about what he was feeling.

All I got in return was a confusing “Yeah.” I stuffed my earbuds in and walked away.

The interior of the Treasury was so small that normal chatter echoed against its walls, creating a reverberating noise. I quickly powered up my iPod and used the song as white noise while I ruminated in mental solitude. I thought about giving myself the space to experiment and create some sort of art after I was blind, but I wasn’t keen on the idea of releasing that work. How could I trust my hand to paint my memories in an accurate way, and with meaning, if I couldn’t see what I was painting? How could I connect fully to the piece if I couldn’t skillfully control the images? And if I couldn’t completely connect with my work then how could I expect anyone else to? The thought of having to start over and redefine my artistic voice was overwhelming. And even more horrifying was the thought of whether or not my new work would be accepted by the art community.

With all of the other tourists around, it was difficult to sit with my thoughts, let alone get a sense of the space. Along the left wall, I found the seats Atef mentioned carved out of the rock surface. I sat, turned my head to the far right, then did a slow sweep of the room, mentally taking a panoramic photo. When I was done, I closed my eyes and sketched in my mind’s eye its dimensions, without the distracting people who obstructed my view.

I tried to stay focused on the art and history before me, but all I could concentrate on was the darkness. Two months didn’t seem like nearly enough time to transition from seeing to not seeing. It wasn’t even a full season. Every time I thought about being blind I wanted to kick and scream and cry, but I wasn’t a kid and my parents were no longer around to listen. The best I could do was to push it out of my mind. Unlike my parents, who disliked seeing me in pain, life could not be persuaded to change its mind. I thought about all the shallow things I’d wished for before: fame, fortune, and the perfect husband.

Opening my eyes, I saw Atef looking at me from the entrance and smiled. He waved. I waved back, trying to hide my embarrassment, and moved to another part of the cave.

Earlier when he had adjusted his turban, Atef’s dark hair fell across his face and beads of sweat dropped off his sideburns, and I had to stop myself from reaching up and touching his face. As he carefully guided us around rocky terrain, offering his hand to help me when needed, I could tell he was the kind of guy who took care of his loved ones, and in this moment I wanted that to be me.

Forcing myself away from thoughts of self-pity, I lifted my fingers to caress the organic patterns on the wall. Reminiscent of a striped picnic blanket rippling through the air just before being set down on the ground, the hues of red (ranging from a pale salmon to a deep crimson) made me think of Rusty. He raved about a Brazilian artist, Henrique Oliveira, whose paintings mimicked the movement in rock formations. Oliveira’s famous technique was to use a non-blending viscous paint mixed with pigments that he stirred in to create his palette. His work was also the inspiration for one of Rusty’s most famous paintings, Seasons. Cubist in design, the piece broke apart the human body and reconstructed it to show different angles at different times. Seasons was a metaphor for the stages of our lives and how time plays an important role in our connections with one another.

Transfixed by the colors in the rock, I did my best to capture their natural tone in the photographs I took. I hoped these hues might lend themselves to an idea I had been turning over in my head since we arrived in Petra. I didn’t know what the central image would be yet, but I did know that whatever landscape I painted in Jordan needed to consist of these same raw shades.

“Hey,” Jeff said, coming up from behind me. “Are you ready? It’s time to go.”

“Hey, are we okay?” I asked him.

“Yeah, why wouldn’t we be?”

“No reason,” I replied, not quite believing him, but also not wanting to pick a fight where there wasn’t one.

That night, we grabbed our overnight bags from the trunk of the car and followed Atef to our campsite. Part of Atef’s two-day tour was a night’s stay in a tent city. Small flickerings of tea lights tucked into the rock lined our walkway, and at the entrance a huge sign read “King Aretas Camp.” Just beyond where we stood were white, cloth-covered wigwams, lined up into organized blocks. The isolated area looked like a forgotten Bedouin civilization.

With Atef still in the lead, we were greeted by our enthusiastic host, Enmar. He was a short but stout man in his early fifties, dressed in a bright blue and green button-down shirt, and light, beige drawstring pants. As he led the way to our tent, we passed by a large area with ornate coffee tables, fluffy sitting pillows, and shaggy rugs begging to be sprawled out upon. I made a mental note to return to this spot later.

Our personal tent was simply furnished with two twin beds, a nightstand, coat hanger, and a large mirror in one corner. I couldn’t wait to plop down and relax, but before I could even sit, we were ushered out for a white tablecloth dinner buffet. The cooks served up an international cuisine of fried rice, broccoli stir-fry, spaghetti, lamb curry, flash fried fish, humus, baba ghanoush, olives, pickles, and the national dish of Jordan: Mansaf, a staple food made of lamb cooked in fermented, dried yogurt and served over a bed of rice. The feast was far more elaborate than I expected for camping and gave new meaning to the term “luxury camping.” Or perhaps was the definition of it.

After a hot shower in simple stone stalls equipped with organic soaps, Jeff grabbed his laptop as I grabbed my sketchbook and we headed for the cozy communal area under the stars.

“Come, join us!” Atef said, beckoning us towards him and Enmar.

“You like him don’t you?” Jeff asked.

“Atef? What’s not to like? He’s attractive and he lives here, where I don’t have to ever see him again.”

“How convenient, I never pegged you for a one-night-stand-type of girl,” Jeff said.

“You’re one to talk,” I said, but before Jeff could answer Atef called to us again.

“Come over! My friend here was just about to tell me stories,” Atef said.

I hadn’t realized it before, but the centerpieces, which I assumed were coffee tables, were actually small pits filled with burning coal—innovative!

“I guess camping anywhere in the world i

s pretty much the same then,” Jeff said.

“In America, you do this too?” Atef asked.

“Absolutely, when we go camping it’s very similar to this with the fire in the center and one person telling stories. But it’s not quite this fancy,” I told Enmar.

“Thank you,” Enmar smiled.

As the night progressed, we sipped single malt whiskey while Enmar told us about the “real” history of Petra: secret maps leading to buried treasure; a golden phoenix; strange sightings in the night sky; and most recently, a larger-than-life ten-foot-tall male skeleton. Our host told these stories with such passion and avidity that I found myself buying into the possibility of a great treasure in Petra. He made me think that maybe the guy who wrote Indiana Jones wasn’t just making it all up. By the time he was done, I was certain that Petra was full of riches, but I believed it to be in spirituality rather than in gold.

The few times Atef and I caught each other’s gaze, I was certain there was something there. He had such dark, intense features that it was hard to tell what he was thinking, and for a while I felt very self-conscious about the way I was sitting, what I was saying, and my overall appearance. To help myself unwind, I drank my first cup of whiskey in one gulp, and Enmar poured me another.

They asked us where we were from and what we did. Jeff told them he was happily unemployed but working on a new project. I told them I was an artist and they immediately handed me a pencil and paper so I could draw their portraits. They told me they would proudly boast about having an original Aubrey Johnson because they met me on my journey and one spontaneous night I “created a masterpiece” of them. How could I say no?

“You are the most beautiful painter…I have ever met,” Enmar slurred.

I blushed. “Not a fan of Hani Alqam?”

“You have heard of Alqam?” Enmar asked. He seemed shocked.

“I wrote a paper on one of his paintings. It was a black and white painting of the backside of a girl bent over while undressing. Such a vulnerable moment to be captured rather grotesquely, I thought. Her flesh was made of thick clumps of acrylic paint so her body appeared inverted, her insides being the components of her exterior. By positioning her in a vulnerable pose of undressing and further exposing her unsavory insides, Algam forced the viewer to address the frailty and complexity of the human psyche, by stripping away all layers of deflection. I think I was drawn to him because I was fascinated by how much a work of art could disturb me,” I smiled.

Blue Sun, Yellow Sky

Blue Sun, Yellow Sky